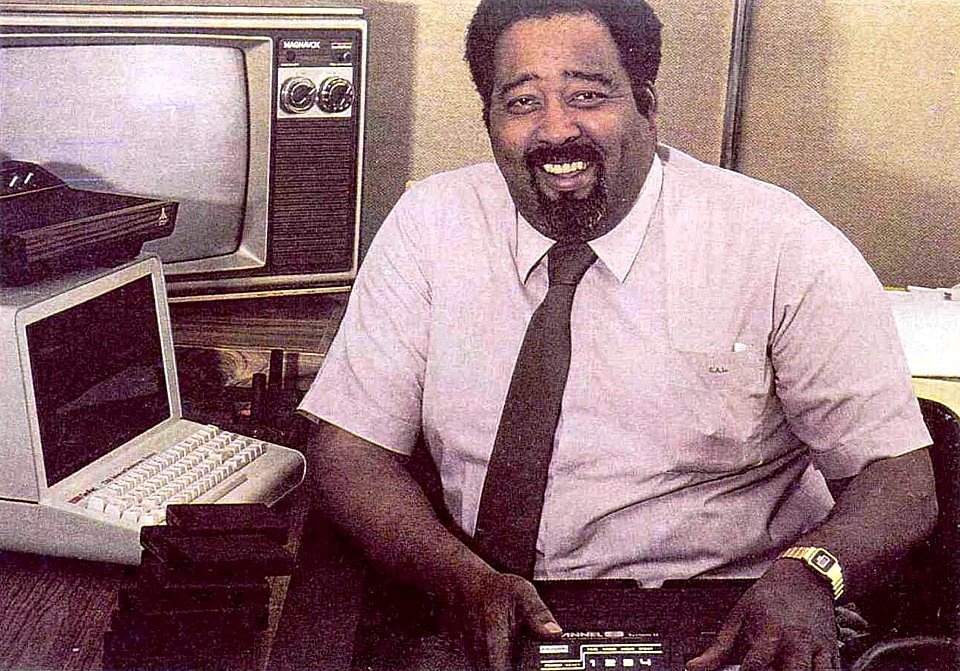

For a long time one of the greatest obstacles to the social acceptance of computing as part of daily life was the insularity and even elitism that prevailed, and to an extent still prevails, among the gatekeepers of computer technology. While the original “tech geek” culture was in large part created by people who felt like misfits and outsiders, these were also people who were themselves almost universally young, white and male. Even today those who share a passion for computing but lack the stereotypical personal traits that many associate with it often feel alienated and marginalized, even from those with whom they have the most in common intellectually. One of these misfits among misfits was Jerry Lawson, one of the few black computer pioneers in history and the designer of the Fairchild Channel F, the pathbreaking console that started the second generation of home console games.

Gerald Lawson was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940, and grew up in a federal housing project in Queens. His father, a longshoreman, would bring home unusual toys for him to play with, and at a young age he developed an interest in electronics, building walkie-talkies and tinkering with a ham radio station that broadcast from his room. As a teenager he repaired TVs to make some extra money, which he spent not on records or clothes but on radio parts. He eventually enrolled in Queens College to study electronics, but like many computing pioneers he left school without a degree.

Lawson had spent his whole life on the East Coast, but a job opportunity at Kaiser Electronics pulled him across the country to California, where he worked on heads-up displays for the military. While working at Kaiser he began to specialize in the use of semiconductors, at that time a new and rapidly changing technology. His specialized knowledge ultimately brought him to the attention of Fairchild Semiconductor, which hired him in 1970 to work as an engineering consultant for their sales division. This job, which involved working directly with the firm’s customers, gave him the chance to see design and technology issues from the end user’s perspective. It also made him uniquely qualified to create and sell a major consumer product from a company that had never aimed at the consumer market before.

Throughout his career up to this point, Lawson had continued to tinker at home. Shortly after he went to work for Fairchild he designed a coin-operated arcade game called Demolition Derby, working out of his garage. His employer wasn’t pleased to see him doing freelance work in a field so close to theirs, but at the same time they recognized that his mastery of this emergent technology was something that could be quite valuable to them. By the mid-70s he had become Chief Hardware Engineer at Fairchild and was the head of a new, bleeding-edge project with the potential to transform their business: a video game console designed for the home.

There had been attempts at video game consoles before, such as the Magnavox Odyssey in 1972. But the Odyssey had been an extremely simple device, practically a toy. It did nothing but display a single vertical line and three movable dots on a television screen, and its “games” were heavily reliant on physical props and overlays, an external score sheet kept by the players, and a hefty amount of imagination. The new Fairchild console, as conceived by Lawson and his team, would be something quite different. It would use microprocessors to give its games virtual memory and a rudimentary kind of artificial intelligence, and these games would appear on ROM-based cartridges that could be easily swapped in and out of the console. Unlike the many dedicated Pong consoles of the early ‘70s, this new device would play more than one game; in fact, the number of games it could play was limited only by the ingenuity of future game designers.

Despite a daunting price tag of $169, equivalent to about $750 today, the Fairchild Channel F (the “F” stood for “Fun”) was a modest success when it came out in 1976, and it probably would have continued to dominate the market in the late ‘70s if not for the doggedness of its competitors. Nolan Bushnell of Atari saw its success and sold his company to Warner Communications for enough funding to fast-track his own home console project, the Atari VCS, which launched almost exactly a year later. The VCS, later known as the Atari 2600, incorporated all of the Fairchild Channel F’s advancements and ultimately became the console of choice for the general consumer. Ironically, Lawson had ended up too far ahead of the curve and not enough at the same time; too far ahead to have a stable market and refined technology, but with a competitor right behind and preparing to leapfrog him.

Lawson’s experience with the computing world was often one of standing alone in a field full of sharp competitors. For some time he was the only black member of the Homebrew Computer Club, famous for its association with Apple founders Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, and the absence of black colleagues in the electronics industry did not escape his notice. He was also confronted more than once with the spectacle of people who knew him by reputation being shocked, upon meeting him in person, to find out that he was black. The idea that a successful computer engineer could be anything other than a bespectacled white guy had never occurred to them before; one man even told Lawson that his voice “sounded white”.

But Jerry Lawson was determined to break the mold. He had been able, through his own hard work, to make a career out of his favorite hobby. He had led the design of a consumer product that was truly innovative and spurred further innovation in his competitors. Without his influence, there may not have been a cartridge-based home console in the ‘70s at all, and the whole history of video gaming would be radically different. The people who have broken color barriers in sports are often well-known and celebrated, but just as important are those who, like Lawson, broke the color barriers of culture.

Next Post: Althea Gibson, the athlete who broke tennis’ color barrier, with a sidelight on her mentor, the physician and “godfather of black tennis” Robert Walter Johnson.