Sometimes our mistakes can be more valuable to us than our successes. They can make us more aware of the intricacies of day-to-day problems and lead us to innovative new solutions. But this can only happen if we acknowledge our mistakes, rather than covering them up and pretending they never happened…well, mostly. In fact, one enterprising woman built a company on the foundation of covering up people’s mistakes, typographical mistakes to be specific. Countless memos owe their smooth, professional appearance to a few choice applications of Bette Nesmith Graham’s correction fluid over those stubborn, set-in-stone typos. And Graham herself would never have invented Liquid Paper if she hadn’t been both a good painter and a pretty mediocre typist.

In a business world dominated by computers, it’s difficult for most people to appreciate the difficulty of producing decent copy on a typewriter. Mistakes in a word processor can be corrected with the press of a single button, while typewriters proudly stamped every bad keystroke onto the paper in quick-drying ink. Errors were essentially permanent and could be removed only with messy and unreliable erasers. An author could submit a manuscript with a few typos in it, knowing that proofreaders would correct the final copy, but in the business world what came out of the typewriter often was the final copy, and professionalism was paramount. The result was a lot of frustration among typists like Graham.

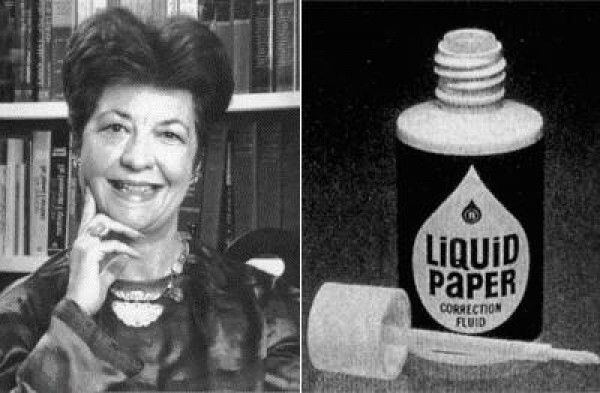

Bette Nesmith Graham was born Bette Clair McMurray in Dallas, Texas on March 23, 1924. She married early and unhappily after dropping out of high school; her husband, Warren Audrey Nesmith, left to fight in World War II shortly after their marriage and divorced her within a year after the war was over, leaving her with few prospects and an infant son to take care of. In need of a job, she moved with her mother and sister back to the family home in Dallas and found employment as a bank secretary. She proved to be an efficient secretary, eventually working for the chairman of the board, but the one aspect of her job she couldn’t master was typing.

Unlike many of the achievers we’ve seen so far, Graham didn’t choose her profession based on personal interest or talent. She found her job uninspiring, and she found much more fulfillment in the extra work she was able to get painting the bank’s windows for special occasions. Paint was her passion; it gave her a connection to the world of fine art, and even better, if you made a mistake you could just paint over it. If only she could do the same with paper and ink!

And that’s exactly what Graham proceeded to do. She filled a bottle with tempera paint and took it with her to work, dabbing it lightly over the typos with a watercolor brush. The fast-drying paint looked just like the paper surrounding it and left a clean white surface to type on. It was as if the mistake had never existed. Soon her co-workers discovered her “Mistake Out” and asked her to make some for them, which she did using her kitchen blender.

For five years “Mistake Out” was used only by Graham and her co-workers at that Dallas bank. Her bosses usually didn’t notice the paint at all, but when they did several of them weren’t pleased at what they saw as an unprofessional fix for substandard typing. When she began trying to market the paint on her own time, they were even more upset, seeing her entrepreneurial activities as a distraction from her duties at the bank. Eventually she made the mistake of signing a memo with the name “The Mistake Out Company”, and the outraged managers decided to fire her. She now had the opportunity, and the urgent need, to turn her renamed “Liquid Paper” into a commercial success.

Sales were slow at first, but as her formula improved and news of the product’s usefulness spread through the business world, the Liquid Paper company grew enormously. Operations moved from Graham’s kitchen to a trailer, then finally to headquarters in downtown Dallas. By the mid-70s several imitators and alternate solutions had sprung up, such as Wite-Out and IBM’s “self-correcting” Selectric II typewriter, but Liquid Paper was still selling around 25 million bottles of correcting fluid a year. When she sold the company to Gillette in 1979, its value had sprung up to almost $50 million.

Bette Nesmith Graham took a weakness and turned it into a career. Frustrated with the slow and messy erasers at her office, she invented a better solution to take their place. Even today, when most documents are written on a word processor, correction fluid is still an essential product that almost everyone who works in an office knows and uses. As both an inventor and an entrepreneur Graham showed perseverance and made herself a success.

As a side note, Graham is not the only famous person in her family. Her son Michael Nesmith, who grew up in a single-parent household and dropped out from high school as well, ultimately found success as a songwriter, a guitarist…and one of the Monkees.

Next Post: Phoebe Ann Moses, sharpshooter and advocate of female independence.