In this series we’ve looked at many entrepreneurs whose hard work resulted in small victories, which then built the groundwork for greater success in the future. However, as we recount these successes we should bear in mind that failure is also a major part of the entrepreneurial experience. Around 20% of new businesses in the United States fail within their first year of operation. By the time five years have passed, that figure rises to about 50%. Entrepreneurship is a process of experimentation, and no matter what field one is in there are always experiments that don’t pan out.

Laws which allow a debtor to declare bankruptcy are not often considered a lynchpin of the economy, but in many ways the modern business landscape would not be possible without them. Before these laws existed, the state’s usual approach to debtors was to throw them in prison to work off their debt, a brutal and often ineffective punishment that ruined the lives of many over a simple reversal of fortune. Such a fate would have prevented the eventual rise of many of America’s greatest citizens, including the future presidents Abraham Lincoln and Harry Truman, as well as the subject of today’s story.

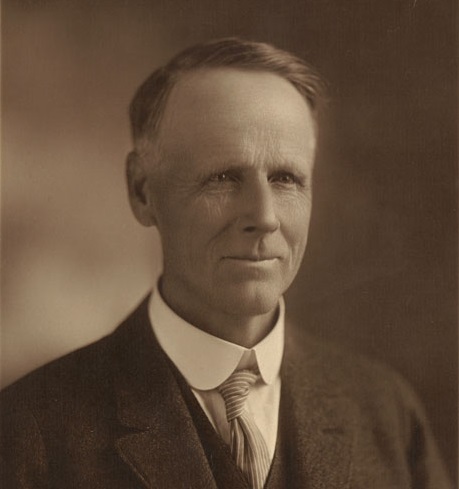

Simon Bergerson Klæve was born on September 9, 1851 in Gausdal, a small town in southern Norway. In his mid-teens his family immigrated to the United States, settling in Black River Falls, Wisconsin and in the process changing their surname to “Benson”. Simon Benson worked as a farmhand and logger for several years, carefully saving his money in the pursuit of a typical American dream: running his own business. By age 24 he had saved up enough to open a general store in nearby Lynxville, which did well for several years.

Then, one day, a fire broke out in his store and destroyed everything: the building, his merchandise, and all the money he had invested in it. Benson, who by this time was married and had an infant son to take care of, was left destitute. All he had left was his knowledge of the logging industry, which he determined to put to good use by moving his family to Portland, Oregon, the center of a rapidly growing timber industry. Benson flourished in Oregon, building up the capital he needed to acquire timberland and go into business for himself.

Benson introduced several innovations into the business that lowered his operating costs significantly. The traditional method of logging up to his time had been to use teams of oxen to drag logs across makeshift “skidroads”, greasing the logs’ path to speed up the process. Benson replaced the skidroads with narrow-gauge railroads, and the oxen with “steam donkeys”, small industrial winches that could work all day and all night. He was the first operator in Oregon to adapt these new technologies to the logging industry, and within a decade his new approach had made him a very wealthy man. His most revolutionary invention, however, came more than a decade later, in response to the booming population of turn-of-the-century California.

In 1906, Benson decided to build a sawmill in San Diego to provide timber to southern Californian cities. He faced a serious problem, though: San Diego, unlike the heavily forested Pacific Northwest, had practically no raw lumber to be milled. Benson had to find a way to economically transport thousands of tons of wood from his logging operations in Oregon to southern California. His solution was a “log raft”, constructed from hundreds of huge logs held together with heavy chains. Log rafts had been used on a small scale to transport lumber down rivers for decades, but Benson was proposing to build massive rafts, nearly an acre in size, and haul them across the ocean.

Many onlookers shook their heads, certain that his rafts would break up and sink, bankrupting him in the process. In the event, only two of the 120 rafts he eventually built were lost, and the venture turned out to be an immense success that lowered lumber costs and sustained the California building boom for the next decade. Benson had proven that he had extraordinary business acumen in every part of the lumber industry, from tree to log to board.

However, Benson’s astuteness wasn’t limited to his business ventures. He also put it to work for philanthropic purposes later in his life. In 1913, for instance, he was pitted against the Portland-based developer George Wetherby in a dispute over the nearby Multnomah Falls. Wetherby, who had leased the land around the waterfall for several years, wanted to build a hydroelectric power plant there; Benson, along with many of Portland’s citizens, wanted to preserve the falls’ beautiful natural scenery and keep the land from being developed. Rather than engage in a lengthy legal battle, he simply purchased the land from its original owner and donated the title deed to the city, allowing the falls to be turned into a public park.

The same year, Benson used charity to solve one of his own labor issues. For many years he had observed some of his workers showing up to the factory drunk. To Benson, who was a teetotaler, this was a disturbing sight that raised concerns about the quality of his employees’ work. After a bit of reflection, he concluded that punishing the offending workers wouldn’t eliminate the source of the problem. Instead, he proposed to take the opposite approach: offer the beer-drinkers a free alternative. With this in mind, he offered Portland’s government $10000 to install public water fountains throughout the city. These unique “Benson bubblers” are still an icon of downtown Portland, and provide over 100,000 gallons of drinking water to the city’s residents every day.

Simon Benson was a lifelong entrepreneur. Even after “retiring” in the 1920s, he soon got involved with property management and began a second career that lasted the rest of his life. However, he was far from a narrow-minded businessman, focused only on profits and the bottom line. He was never afraid to invest his money in the community, taking his dividends in the form of increased civic spirit and greater opportunities for his fellow citizens. It is telling that of the West Coast “timber barons” who made fortunes in the logging industry, only Benson is remembered to any considerable extent today.

Next Post: Jessie Redmon Fauset, the novelist and editor who rose from humble origins to become a leading light of the Harlem Renaissance.